The Workforce Outcomes of Physicians Completing Residency Training in North Carolina in 2017, 2018, and 2019

By Evan Galloway, Brianna Lombardi, Erin P. Fraher

Jun 30, 2025

Introduction

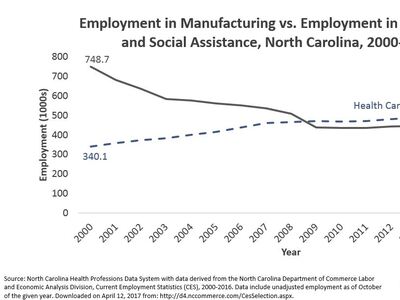

Graduate medical education (GME), commonly referred to as “medical residency” or “residency,” occurs after medical school. After graduating from medical school, physicians complete a residency to gain skills and competencies in a particular area of medicine, for example, family medicine, obstetrics and gynecology (ob-gyn), or general surgery. Both allopathic (MD) and osteopathic (DO) physicians must complete medical residencies to become fully licensed to practice medicine by the North Carolina (NC) Medical Board. The length of a medical residency depends on the specialty, with most residencies lasting between three to seven years.

Most funding for residency training in NC and the nation comes from Medicare. Other funding sources include the United States Department of Veteran Affairs, Health Resources and Services Administration, Medicaid, state appropriations, and hospitals. NC’s Medicaid program provides a greater amount of GME funding than most other states.1 In 2018, NC ranked fifteenth among all 50 states and DC in GME funding provided by Medicaid, with a total of $100 million in annual GME support.1 Despite the relatively high investment of state funds in GME in NC, there are no required accountability measures attached to these monies. The lack of transparency and accountability for public investments in GME is not unique to NC; it has been identified as a major flaw in the system by numerous reports.234 Without accountability for funds, NC and the nation are unable to target GME investments to ensure that training programs produce the workforce necessary to meet population health needs.

This report builds on prior work conducted by Sheps Center researchers, including a prior edition of this report, two national studies of state level GME reform focusing on Medicaid GME,56 a report on GME tracking efforts in NC,7 and a study of the possible effects of expanding or reallocating GME positions on the supply of physicians.8

Methods

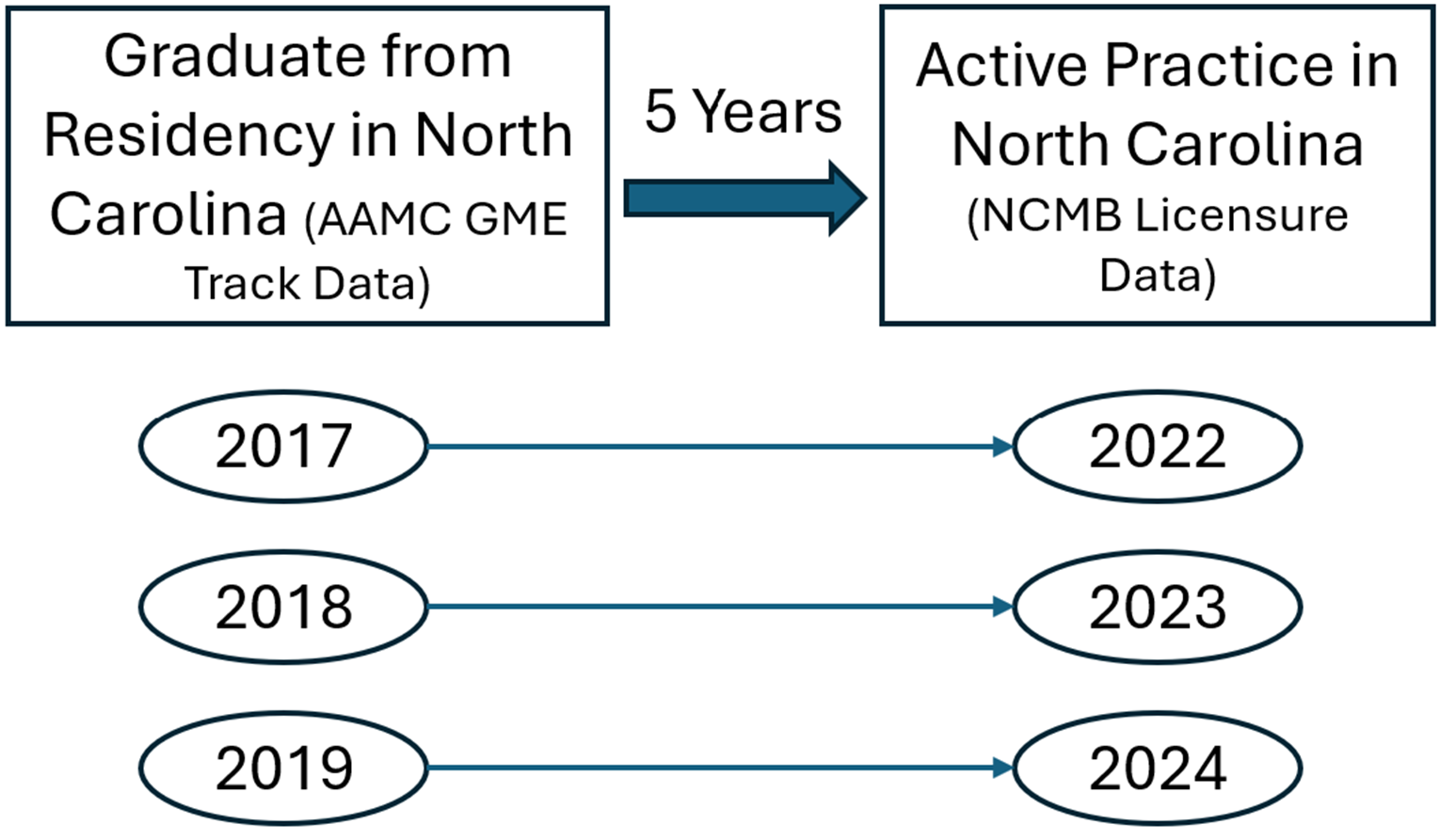

Using a cohort study design, we analyzed the number and percent of residency and fellowship program graduates who completed training in 2017, 2018, and 2019 who were in practice in NC and in rural areas five years after residency or fellowship graduation. We also examined the number and percent of physicians who completed residency training in NC who were in practice in NC five years after training for seven high need specialties: ob-gyn, family medicine, general internal medicine, internal medicine/pediatrics, general pediatrics, psychiatry, and general surgery.

Data and Analysis

To evaluate the return on investment of residency programs’ contributions to the NC workforce, as measured by the number of physicians retained to practice in NC, we tracked three annual cohorts of NC GME graduates in active practice in NC five years after they completed residency or fellowship training (Figure 1). To identify graduates from NC GME programs in 2017, 2018, and 2019, we obtained National Graduate Medical Education Census (GMETrack) data, housed at the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC).9 GMETrack includes a survey of residents on duty in December of each year in programs accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).9 GMETrack is called a “census” of US based residents but the data are survey data and most, but not all, GME programs complete the survey. As such, only GME graduates in GMETrack are included in our analysis. GMETrack also includes data on the location of the physician’s medical school which allowed us to examine differences in retention for NC medical school graduates compared to out-of-state medical school graduates.

Figure 1. Cohort Approach to GME Tracking

GMETrack data were merged with the NC Medical Board’s annual licensure file maintained by the NC Health Professions Data System (HPDS). The HPDS data include licensed physicians in active practice in 2022, 2023, and 2024 with a primary practice address in NC who are not practicing under a resident license and are not employed by the federal government as of October 31st in each year. HPDS data identify a physician’s self-reported primary area of practice which may be the same as the physician’s specialty (e.g. internal medicine, neurological surgery, or dermatology) but may also correspond to the physician’s area of work (e.g. hospitalist, urgent care, or student health).

We geocoded practice addresses reported in the HPDS licensure data to determine the characteristics of a physician’s practice location. Physicians were coded as practicing in a rural area if the primary practice location was in either: a) a non-metropolitan county according to the 2023 federal Office of Management and Budget (OMB) classification, or b) a metropolitan county in an area with a 2010 Rural Urban Community Area (RUCA) code of four or greater. The NC Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) maintains a list of safety net sites, which was most recently updated in July 2024, and was used to identify physicians practicing in safety net facilities.10 To determine the socioeconomic status of the neighborhoods in which residency graduates are practicing, we used the 2022 vintage of the Area Deprivation Index (ADI) produced by the University of Wisconsin Center for Health Disparities Research.11 We used the version of the index which is calculated relative only to areas within the state, not the entire nation. As such, this index compares areas within NC to each other. A state ADI of 9 or 10 represents the top quintile of neighborhood deprivation within this index and is what this report refers to as “the most deprived neighborhoods”.

Data were analyzed to determine physician outcomes five years after graduation including retention in NC, practice in rural NC, and practice in high need specialties (defined in this report as general internal medicine, family medicine, general pediatrics, general surgery, ob-gyn, psychiatry and internal medicine/pediatrics). Because many residency programs have only a few graduates each year, outcomes for multiple years (2017, 2018 and 2019) were combined to increase the sample size. This analysis generated data that indicates, for each residency program in NC, the number (and percent) of residency program graduates that are in practice in NC and in rural areas.

Cohort Analysis Findings

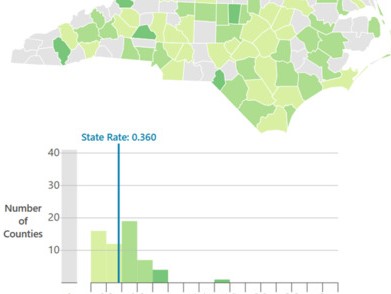

Table 1 shows the workforce retention outcomes by cohort. On average, across all three cohorts, 37.1% of NC GME graduates were practicing in NC five years later and nearly 3% were practicing in rural NC. These data suggest that a decreasing percentage of residents were retained in NC in recent years, down from nearly 40% of the 2017 graduates to 36% of 2018 and 2019 graduates.

Table 1. Number and Percentage of NC GME Graduates in Active Practice in NC and rural NC Five Years After Graduation by Cohort

| Residency or Fellowship Graduation Year | Number of NC Residency or Fellowship Graduates | Number (%) Retained in Active Practice in NC Five Years Later | Number (%) Retained in Active Practice in Rural NC Five Years Later |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 1,145 | 457 (39.9%) | 39 (3.4%) |

| 2018 | 1,197 | 430 (35.9%) | 28 (2.3%) |

| 2019 | 1,264 | 452 (35.8%) | 39 (3.1%) |

| Total | 3,606 | 1,339 (37.1%) | 106 (2.9%) |

Data: Association of American Medical Colleges GME Track and North Carolina Medical Board. Physicians are defined as being retained in-state if five years after graduation they have an active medical license, have a primary practice address in North Carolina, and are not working in a federal government setting. Rural practice locations are those within a county that is not part of a Metropolitan Statistical Area as defined by the US OMB in July 2023, or within a Census tract with a 2010 Rural-Urban Commuting Area code of four or greater.

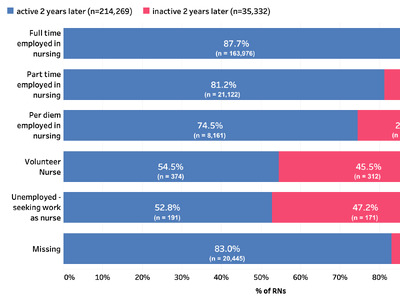

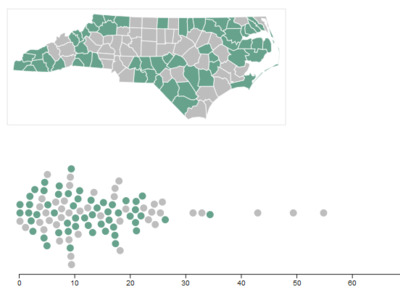

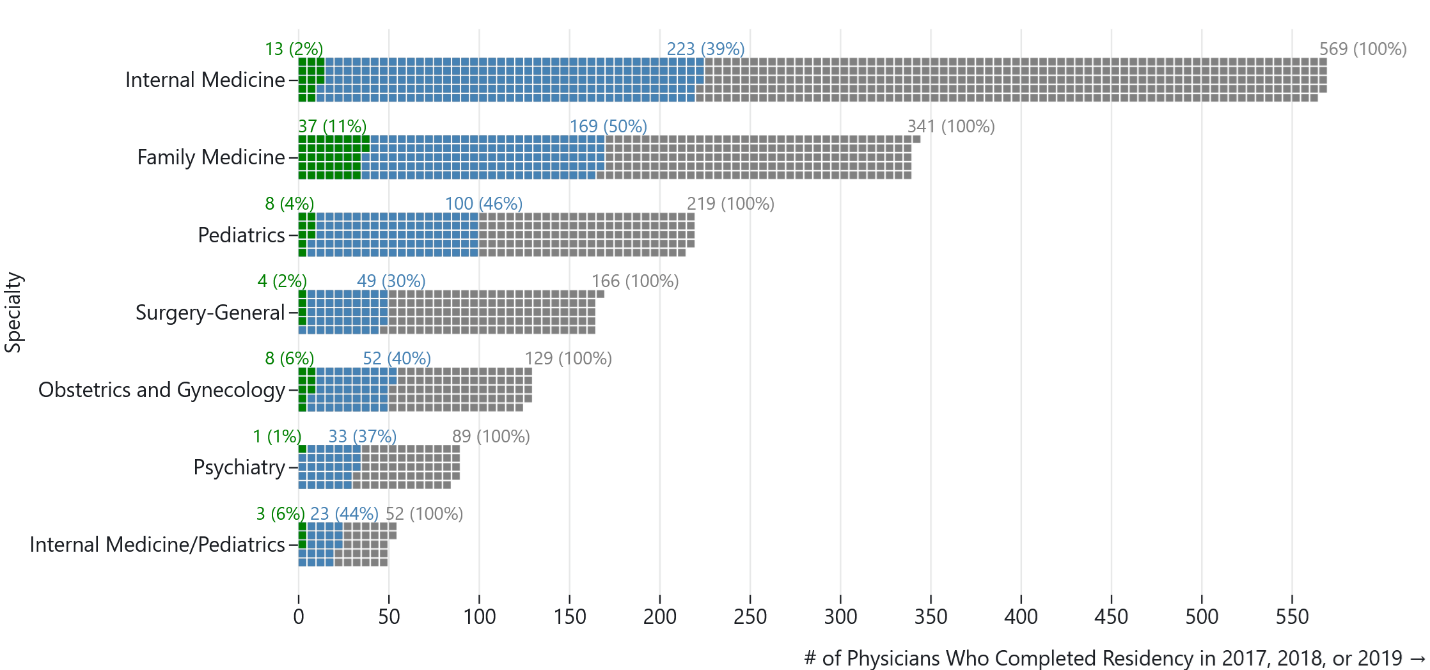

Figure 2 shows the number and percent of residents retained in NC and practicing in rural areas in NC. Internal medicine (IM) is the largest of the high need specialties in NC with a total of 569 residents graduating between 2017 and 2019; 39% of these graduates were retained in state and 2% were in active practice in rural areas five years after graduating. Part of the reason for their lower retention rate relative to other specialties is that IM residents are more likely to pursue further subspecialty training, which may draw them away from the state and out of general internal medicine. Half (50%) of family medicine residents were retained in NC and 11% were in practice in rural areas of NC five years after graduating. Other specialties - pediatrics, general surgery, ob-gyn, psychiatry and internal medicine/pediatrics vary in workforce retention outcomes with general surgery residents having the lowest retention rate in NC five years after graduation (30%) compared to other specialties examined in this report. Psychiatry programs had the lowest rural retention with only 1% of residents in practice in rural areas five years after graduation.

Figure 2. Retention in North Carolina or Rural NC Five Years After GME Graduation for Physicians Graduating in 2017, 2018, or 2019 from an NC Residency by Resident Specialty

Data: Association of American Medical Colleges GME Track and North Carolina Medical Board. Physicians are defined as being retained in-state if five years after graduation they have an active medical license, have a primary practice address in North Carolina, and are not working in a federal government setting. Rural practice locations are those within a county that is not part of a Metropolitan Statistical Area as defined by the US OMB in July 2023, or within a Census tract with a 2010 Rural-Urban Commuting Area code of 4 or greater.

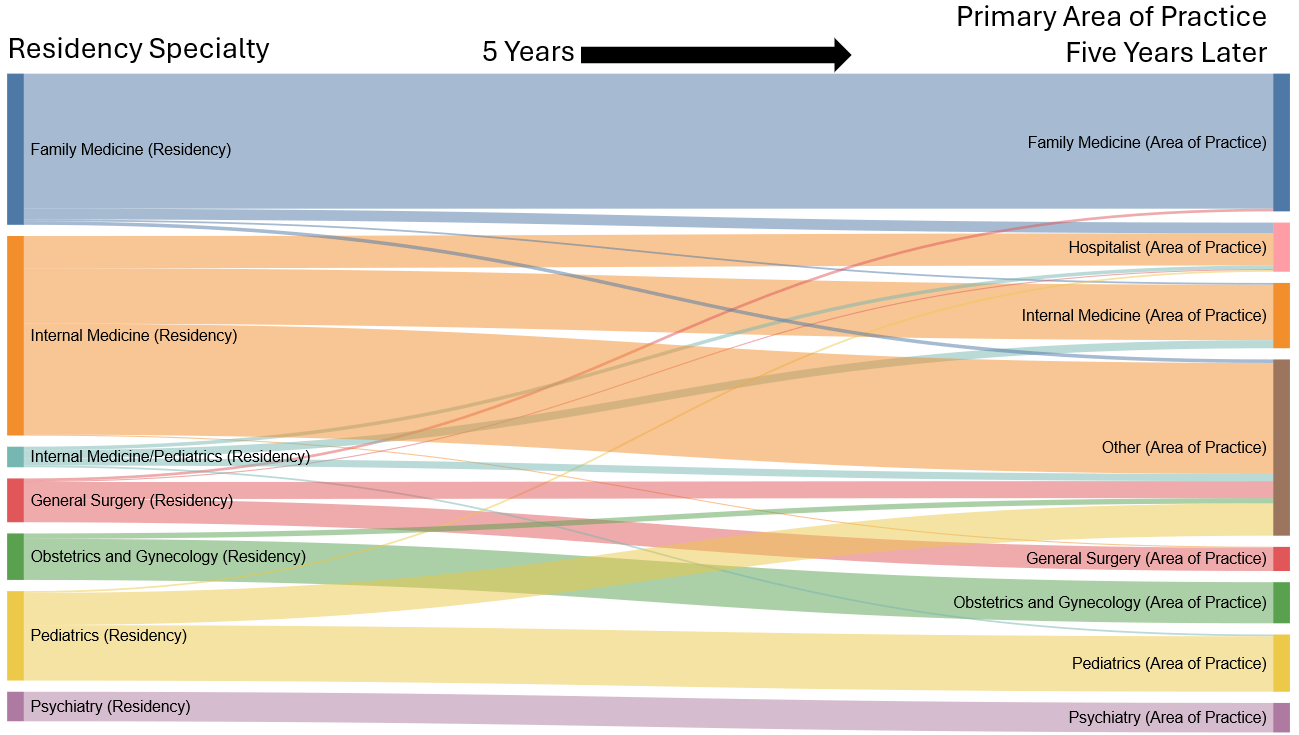

Figure 3 uses a Sankey diagram to show subspecialization rates among NC residents graduating from generalist training programs five years after graduation. IM physicians had the highest subspecialization rates with 72% not retained in general internal medicine, including 16% of general IM residents who became hospitalists and 56% who were practicing in other subspecialties, including IM subspecialties five years after graduation. Nearly half (47%) of general surgeons were not in general surgery five years after graduation, and 38% of general pediatricians were not practicing as general pediatricians. By contrast, only 11% of family medicine residents were not practicing as family medicine physicians and all psychiatrist trainees remained in psychiatry five years after graduating from residency training.

Figure 3. Residency Specialty and Primary Area of Practice Five Years Post-Graduation for Physicians Graduating in 2017, 2018, or 2019 from a NC Residency

Data: Association of American Medical Colleges GME Track and North Carolina Medical Board. Physicians are defined as being retained in-state if five years after residency graduation they have an active medical license, have a primary practice address in North Carolina, and are not working in a federal government setting.

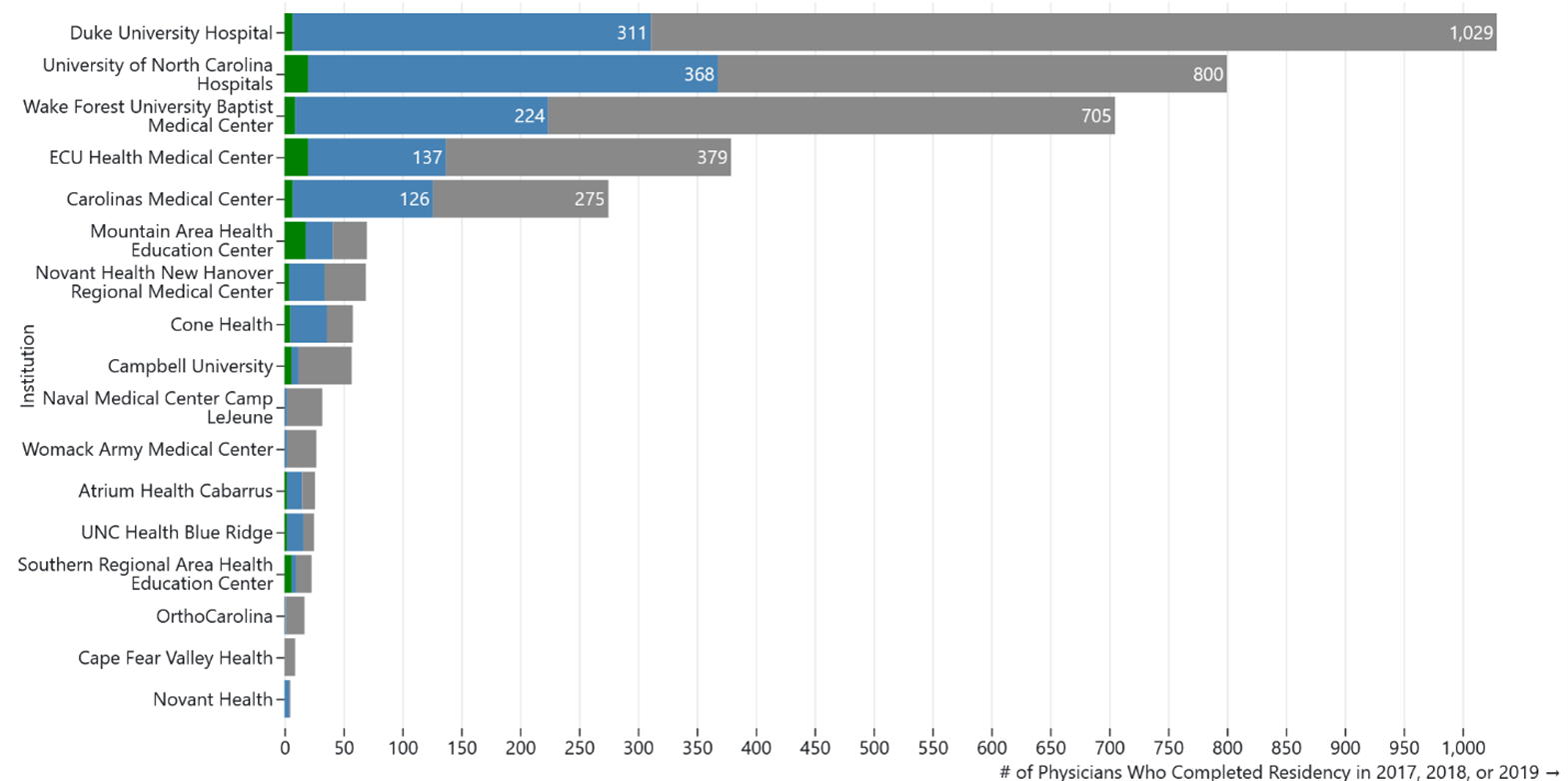

Figure 4 shows the number of residents retained in NC and in rural NC areas by sponsoring institution of GME training. Over the three cohorts, Duke University Hospitals produced the most residency graduates in NC (1,029 graduates), followed by University of North Carolina Hospitals (800) and Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Centers (705). Because these data are aggregated to the sponsoring institution level, these figures include residents training at both at the sponsoring institution, as well as other sites where training occurs for that institution.

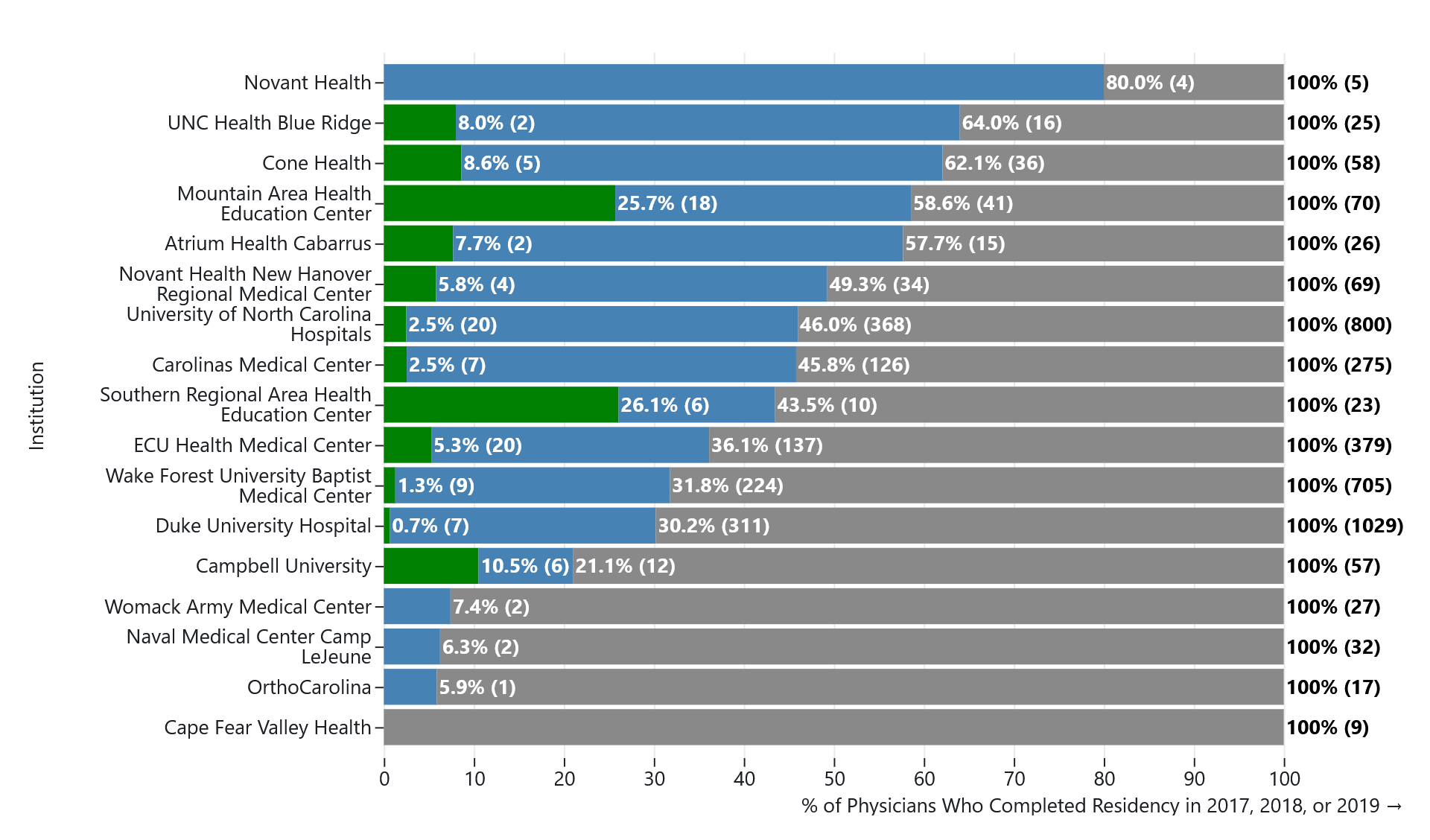

Figure 5 shows the same data as Figure 4 but by percentage of the graduating class. Residencies sponsored by the Mountain Area Health Education Center (MAHEC) and the Southern Regional Area Health Education Center retain the largest percentage of their residents retained in rural areas of NC. MAHEC retains 41% of its graduates in NC and 26% of its graduates in rural areas five years after graduation. Southern Regional AHEC retains 56.5% of its graduates and 26.1% of its graduates in rural areas. Among the larger residencies (greater than 100 graduates across all three cohorts), the University of North Carolina Hospitals retains the greatest percentage in-state at 46%, followed by Carolinas Medical Center (45.8%) and ECU Health Medical Center (36.1%).

Figure 4. Resident Retention in North Carolina or Rural NC Five Years After Graduation for Physicians Graduating in 2017, 2018, or 2019 from an NC Residency by Institution

Data: Association of American Medical Colleges GME Track and North Carolina Medical Board. Physicians are defined as being retained in-state if five years after graduation they have an active medical license, have a primary practice address in North Carolina, and are not working in a federal government setting. Rural practice locations are those within a county that is not part of a Metropolitan Statistical Area as defined by the US OMB in July 2023, or within a Census tract with a 2010 Rural-Urban Commuting Area code of four or greater.

Figure 5. Resident Retention in North Carolina or Rural NC Five Years After Graduation for Physicians Graduating in 2017, 2018, or 2019 from an NC Residency by Institution

Data: Association of American Medical Colleges GME Track and North Carolina Medical Board. Physicians are defined as being retained in-state if five years after graduation they have an active medical license, have a primary practice address in North Carolina, and are not working in a federal government setting. Rural practice locations are those within a county that is not part of a Metropolitan Statistical Area as defined by the US OMB in July 2023, or within a Census tract with a 2010 Rural-Urban Commuting Area code of four or greater.

Another way to look at the outcomes for NC residency graduates is to examine how many are practicing in areas with underserved populations. About 1% (34) of residency graduates were in active practice at a safety net facility as defined by NC DHHS. Residents who completed a family medicine residency represented two-thirds of these physicians. The data reveal that 168 (4.6%) residency graduates were found to be in active practice in neighborhoods in the top quintile of the area deprivation index (i.e. most deprived places).

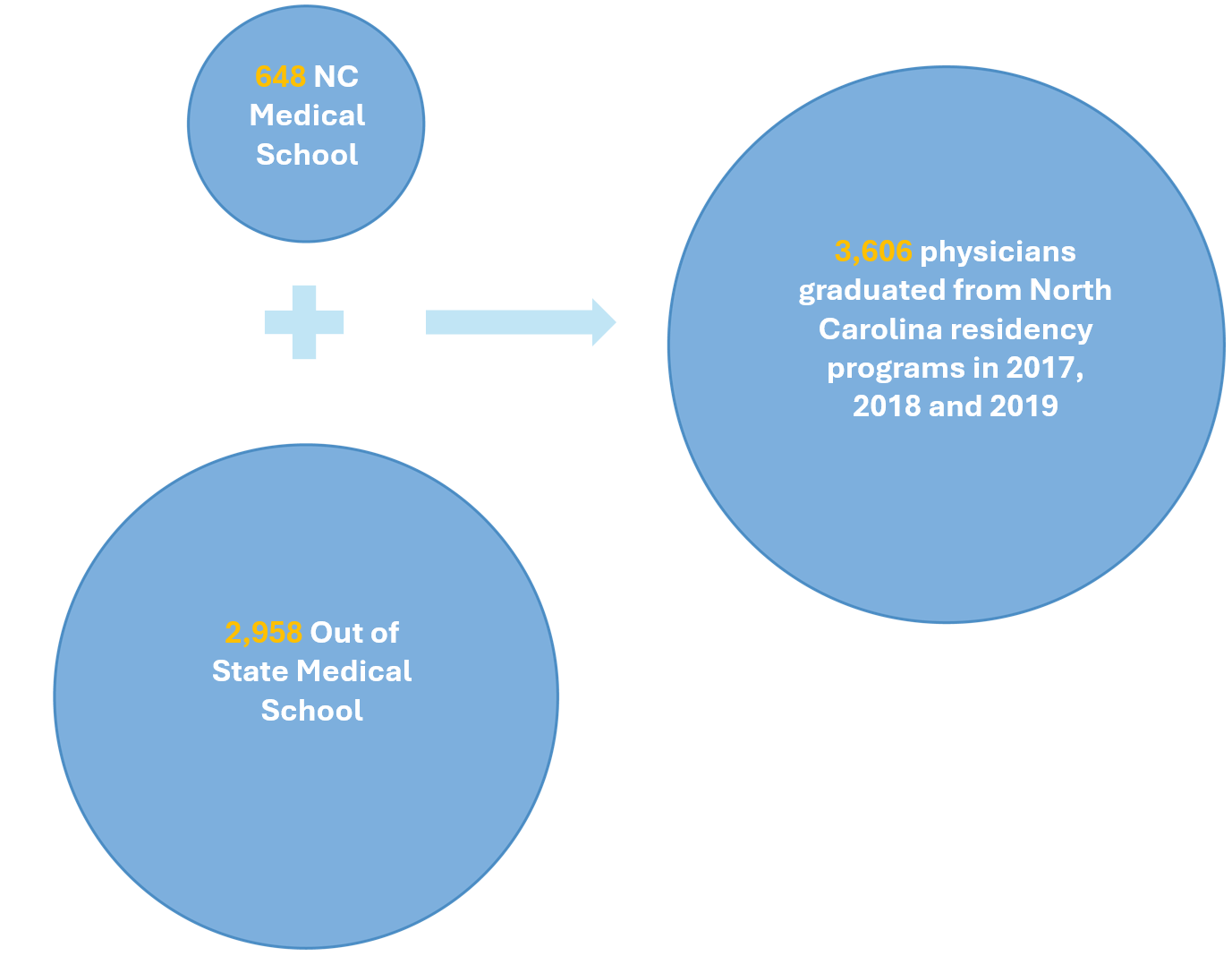

Of the 3,606 physicians who graduated from a NC residency program in 2017, 2018 and 2019, the majority (82%) graduated from an out-of-state medical school (Figure 6). Physicians who attended both an NC medical school and an NC residency have higher retention rates in NC. Across the 2017, 2018, and 2019 cohorts, 648 residency graduates also graduated from an NC medical school and five years later, 64.5% of these 648 physicians were actively practicing in NC and 4.8% were practicing in rural NC. By comparison, the retention of out of state medical school graduates with NC GME training was 31.1%.

Figure 6. Medical School Location of Physicians Graduating from an NC Residency in 2017, 2018, and 2019

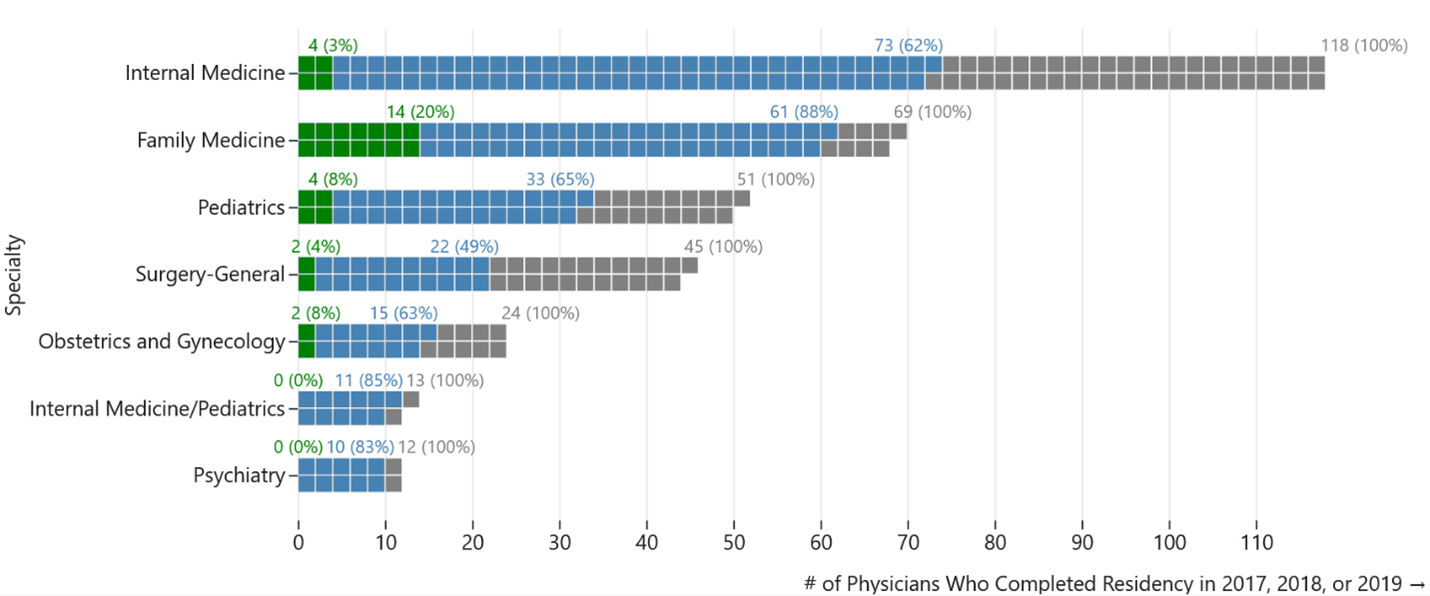

Figure 7 shows the retention rates for these “double NC graduates” by residency specialty. Almost 90% of NC family medicine residency graduates who also attended an NC medical school were retained in practice in NC five years later, and 20% were in active practice in rural NC. While the overall numbers are much smaller for psychiatry and IM/pediatrics residents, those who graduated from an NC medical school also exhibited high in-state retention rates.

Figure 7. Resident Retention in North Carolina or Rural NC Five Years After Graduation for Physicians Graduating in 2017, 2018, or 2019 from an NC Residency who also Graduated from an NC Medical School by Resident Specialty

Data: Association of American Medical Colleges GME Track and North Carolina Medical Board. Physicians are defined as being retained in-state if five years after graduation they have an active medical license, have a primary practice address in NC, and are not working in a federal government setting. Rural practice locations are those within a county that is not part of a Metropolitan Statistical Area as defined by the US OMB in July 2023, or within a Census tract with a 2010 Rural-Urban Commuting Area code of four or greater.

Conclusion

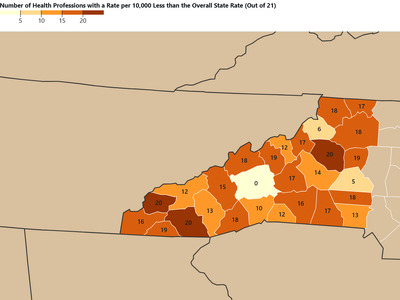

Understanding trends in the retention of residents trained in the state is important to assess the return on investment of public funds spent on training and to assess whether the training capacity in the state is sufficient to maintain or increase the supply of physicians in the state to meet evolving health care needs of NC. North Carolina is one of the few states that systematically reports workforce retention outcomes for all medical students and residents trained in-state using a cohort-based approach. By reporting outcomes at the specialty level in addition to the institutional level, the data reveal significant variation in the proportion of graduates who remain in NC to practice, particularly in rural areas and in high need specialties. This level of granularity provides valuable insights for workforce planning and policy development.

As policy makers consider ways to increase the number of physicians practicing in NC, it is important to have data on which GME programs are retaining their graduates in NC, in needed specialties and in rural areas. Physicians are increasingly subspecializing and fewer are practicing in “generalist” specialties such as family medicine, general IM, general pediatrics, general surgery, and general psychiatry. Increasing rates of specialization among IM physicians12, pediatricians13 and general surgeons1415 limits the availability of generalist health care services to NC’s population. While the state needs subspecialists, maintaining an adequate supply of generalist physicians is necessary to meet demand for primary care, mental health, obstetric and gynecological care, child health, and general surgery services. The data in this report suggest that family medicine GME programs in NC, especially those that recruit trainees who completed medical school in-state, have high retention rates in NC in generalist practice and in rural communities.

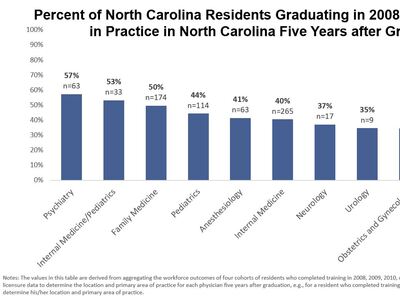

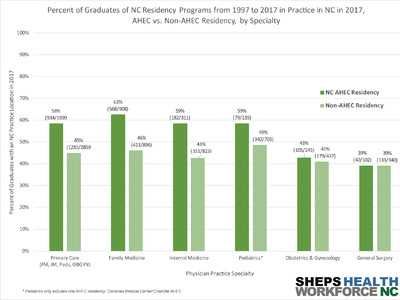

We used a cohort approach for this analysis because it matches the approach used in the 2018 GME tracking report16 and the consistent methodology allows policy makers to evaluate whether the workforce outcomes of NC’s GME programs change over time. Compared to those previous analyses, retention rates have decreased. The 2018 report showed that 43% of graduates who completed GME training between 2008 and 2011 remained in NC; this report showed that percentage had declined to 37% of residents graduating in 2017-2019. There were also differences in retention for specialties in this current analysis compared to 2008-2011. Specifically, there was a decrease in the in-state retention for psychiatry from 57.3% to 33.9% and surgery from 37.1% to 29.5% between the earlier 2008-2011 cohort residents graduating in 2017-2019. In contrast, the in-state retention rate for pediatrics increased from 44.3% to 45.7% and the in-state retention for ob-gyn increased from 34.5% to 40.3%. Also, family medicine graduates in the current report were much more likely to be practicing in rural NC compared to the previous report (10.8% vs 4.8%). Further analyses are needed to explore why this occurred.

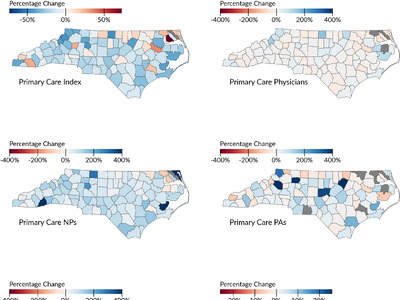

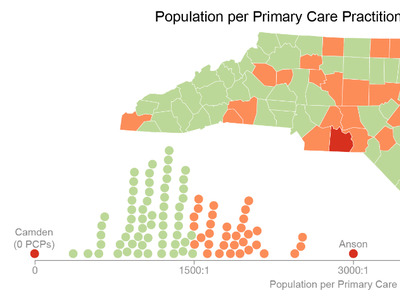

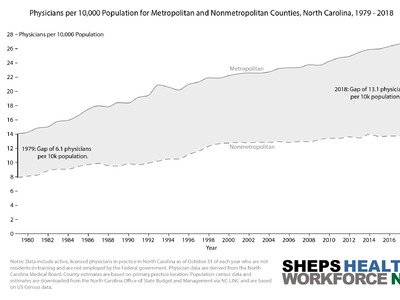

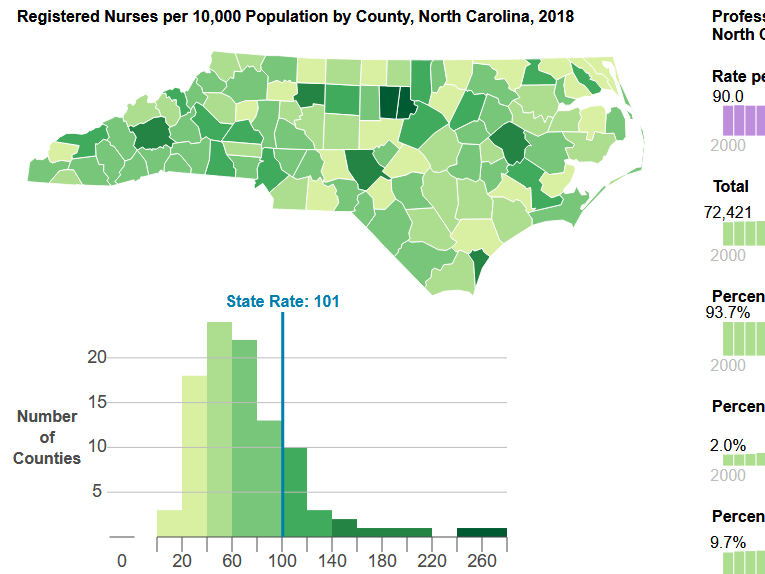

While study findings found an increase in NC trained residents practicing in rural areas in 2017-2019 compared to 2008-2011, there continues to be a gap between the supply of physicians in rural NC counties compared to metropolitan ones. A recent analysis17 released by the Sheps Center found that 24 North Carolina counties did not have a sufficient number of primary care clinicians and that 174 additional primary care clinician FTEs would be needed to bring these counties to the threshold for primary care sufficiency. As the state considers ways to increase residency training in NC by investing in new programs or expanding the capacity of existing programs, policy makers may want to review how other states have implemented accountability measures to assess the return on investment of programs in producing physicians practicing in rural and underserved areas. One state model to consider is Missouri. In 2023, The Missouri General Assembly used state appropriations to fund the expansion of primary care and psychiatry residencies in the state. Selection criteria for these expansion funds include a priority for GME programs that have a proven track record of retaining residents in state and in rural practice after graduation.18

This analysis did not account for the fact that residents, particularly those in specialties like family medicine, may have training experience in rural areas or underserved communities during residency and that this exposure contributes to their higher likelihood of rural practice and practice in safety net settings after graduation. A recent study by Hawes et al. measured trends in the number of medical residency training sites in rural and federally qualified health center (FQHC) settings, using data from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.19 That study showed that the number of residency programs with training in rural areas increased as a result of federal investments in GME through the Teaching Health Center GME and Rural Residency Planning and Development programs. Future analyses could potentially access ACGME data to look at outcomes at the site level and examine how programs with greater rural training are more likely to produce physicians who practice in NC’s rural areas.

Funding

The HPDS is maintained by the Program on Health Workforce Research and Policy at the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, in collaboration with the North Carolina Area Health Education Centers Program (AHEC), and the state’s independent health professional licensing boards. Ongoing financial support is provided by the NC AHEC Program Office. Although the NC HPDS maintains the data system, the data remain the property of their respective licensing board. This information or content and conclusions are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by NC AHEC. To learn more about NC AHEC please visit: https://www.ncahec.net.

References

Suggested Citation: Galloway E, Lombardi B, Fraher EP. The Workforce Outcomes of Physicians Completing Residency Training in North Carolina in 2017, 2018, and 2019. Program on Health Workforce Research and Policy. Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. June 30, 2025.

-

Henderson T. Medicaid Graduate Medical Education Payments: Results From the 2022 50-State Survey. 2023. Accessed October 20, 2023. https://store.aamc.org/downloadable/download/sample/sample_id/590/. ↩︎

-

Institute of Medicine. Graduate medical education that meets the nation’s health needs. 2014. Accessed December 11, 2016. https://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2014/Graduate-Medical-Education-That-Meets-the-Nations-Health-Needs.aspx ↩︎

-

Wilensky G. The challenges of reforming graduate medical education payments. JAMA. Dec 17 2014;312(23):2479-80. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.14751 ↩︎

-

Fraher EP, Rains JA, Bacon TJ, Spero J, Hawes E. Lessons learned from state-based efforts to leverage Medicaid funds for graduate medical education. Academic Medicine. 2023:10.1097. ↩︎

-

Spero J, Fraher E, Ricketts T, Rockey PH. GME in the United States: A Review of State Initiatives. 2013. Accessed June 20, 2025. https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/GMEstateReview_Sept2013.pdf ↩︎

-

Fraher E, Spero J, Bacon T. State-based approaches to reforming Medicaid-funded graduate medical education. 2017. Accessed June 20, 2025. https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/ExecSumm_FraherGME_y3_final-1.pdf ↩︎

-

Newton W, Wouk N, Spero JC. Improving the return on investment of graduate medical education in North Carolina. North Carolina Medical Journal. 2016;77(2):121-127. ↩︎

-

Fraher EP, Knapton A, Holmes GM. A methodology for using workforce data to decide which specialties and states to target for graduate medical education expansion. Health Services Research. 2017;52:508-528. ↩︎

-

GME Track. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2025. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/students-residents/report/gme-track ↩︎

-

Safety Net Sites. North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. Updated July 2024. https://www.ncdhhs.gov/divisions/office-rural-health/safety-net-resources/safety-net-sites ↩︎

-

Kind AJ, Buckingham WR. Making Neighborhood-Disadvantage Metrics Accessible - The Neighborhood Atlas. New England Journal of Medicine. June 2018 2018;378(26):2456-2458. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1802313 ↩︎

-

Anderson RJ. Subspecialization in internal medicine: a historical review, an analysis, and proposals for change. Am J Med. Jul 1995;99(1):74-81. doi:10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80108-9 ↩︎

-

Macy ML, Leslie LK, Turner A, Freed GL. Growth and changes in the pediatric medical subspecialty workforce pipeline. Pediatric research. 2021;89(5):1297-1303. ↩︎

-

Klingensmith ME, Cogbill TH, Luchette F, et al. Factors influencing the decision of surgery residency graduates to pursue general surgery practice versus fellowship. Annals of surgery. 2015;262(3):449-455. ↩︎

-

Stitzenberg KB, Sheldon GF. Progressive specialization within general surgery: adding to the complexity of workforce planning. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2005;201(6):925-932. ↩︎

-

Fraher E, Spero JC, Galloway E, Terry J. The Workforce Outcomes of Physicians Completing Residency Programs in North Carolina. 2018. ↩︎

-

Galloway E. Is Access to Primary Care Clinicians Improving In North Carolina? Nov 4, 2024, 2025. Accessed June 20, 2025. https://nchealthworkforce.unc.edu/blog/pcc_index_2023/ ↩︎

-

Missouri Department of Health & Senior Services. Missouri Graduate Medical Education Grant Program. 2023. Accessed August 30, 2023. https://health.mo.gov/living/families/primarycare/gme/pdf/gme_ngo.pdf ↩︎

-

Hawes EM, Lombardi B, Adhikari M, et al. Physician Training In Rural And Health Center Settings More Than Doubled, 2008–24: Article examines trends in medical residency training in rural and federally qualified health center settings. Health Affairs. 2025;44(5):572-579. ↩︎